The Elgar Society Journal

You can find all articles from the Elgar Society Journal here…

Half Century: The Elgar Society 1951-2001

In 2001 the Elgar Society celebrated its fiftieth anniversary. This event was marked by the publication of a booklet highlighting some of the most important landmarks in the Society’s history. Click here to view.

Journal Library

Notes for Contributors

Anyone wishing to submit an article for publication in the Elgar Society Journal should send the full text to journal@elgarsociety.org . All submissions should follow the Editor’s guidelines, which can be accessed here.

Journal Abstracts

This page shows detailed abstracts of articles appearing in all issues of the Elgar Society Journal since 1999.

| Author | Title | Abstract | Date | Volume | No. | Pages |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moody, Catherine | Arthur Troyte Griffith 1864 ? 1942: Enigma Variation (No VII, ?Troyte?) and Malvern character | Arthur Troyte Griffith, a friend of Elgar?s, was a Malvern-based architect and water-colourist. There are many anecdotes showing his character, and research into his work shows him to have been a practical and gifted architect. | 1999 March | 11 | 1 | 2 to 6 |

| Mandell, Robert | Elgar: The Enigma Variations - Leonard Bernstein conducting the BBC Symphony Orchestra Rehearsal & Performance | The author worked with Bernstein on several occasions, including his recording of the Enigma Variations with the BBC Symphony Orchestra. In spite of the extremely slow tempi, and the resulting bad-tempered exchanges between conductor and orchestra during rehearsal, the orchestra?s playing on the final recording is marvellous. | 1999 March | 11 | 1 | 7 to 10 |

| Neill, Andrew | The Great War (1914 to 1919): Elgar and the Creative Challenge | In common with most creative artists, Elgar was deeply affected by World War I. The Elgar diaries and letters give an insight into the impact of events over the years and the music which Elgar was writing. With the significant exception of The Spirit of England, much of his output during the course of the war was escapist, but with peace came the ability once more to write music of real inspiration, notably the chamber works. | 1999 March | 11 | 1 | 11 to 41 |

| Seal, Hugh | Memories of Elgar and Read | The author studied violin with WH Reed and took part in a performance of The Dream of Gerontius conducted by Elgar. One of his lessons took place just after Reed had heard that Elgar was dying. The author became Rector of Morecambe and was involved with the festival supported many years before by Canon Gorton. | 1999 March | 11 | 1 | 42 |

| Trowell, Brian | ?Bramo assai? : a postscript | A final paragraph as an afterthought to the article "A minor Elgarian enigma solved" (November 1998). This concerned Elgar?s deliberate misquotation of Tasso at the end of the autograph full score of the Enigma Variations, following Elizabeth Barrett?s correct use of the quotation as an epigraph to a volume of poems. The original reads ?Brama assai, poco spera, e nulla chiede?. | 1999 March | 11 | 1 | 43 |

| Still more on Elgar/Payne 3 | A reprint of an article in the Sunday Telegraph (11/98) by Michael Kennedy in which he states that, despite the inevitable questions, we have ?a new masterpiece from a composer whose work we thought we knew in its entirety?. An article by Peter Taylor follows, detailing his own response to repeated hearings of the symphony | 1999 March | 11 | 1 | 43 to 48 | |

| Winter, John | Elgar?s Te Deum & Benedictus | Elgar?s church music rarely receives sufficient appreciation. This work repays analysis and performance: it is meticulous in detail and if the markings are followed it is possible to hear that it is far finer than much of the church music written by his contemporaries and does not deserve neglect. | 1999 July | 11 | 2 | 70 to 74 |

| McGuire, Charles E | Elgar: One story, two visions - textual differences between Elgar?s and Newman?s The Dream of Gerontius | The Dream of Gerontius signalled a departure from compositional tradition, but the importance of its text transcends the uniqueness of its subject. A careful comparison of the original poem and the finished libretto reveals that Elgar radically altered the philosophical thrust of the poem, shifting the focus of the oratorio away from Newman?s vision of the afterlife towards Gerontius as a suffering human figure. | 1999 July | 11 | 2 | 75 to 88 |

| Bury, David | Elgar and Queen Mary?s dolls? house | Elgar was greatly affronted at being asked to provide a piece of music for Queen Mary?s Dolls? House, designed by Edwin Lutyens. Many creative artists made a contribution to this project, which was completed for the British Empire Exhibition in 1924. Ironically, Elgar was very involved in providing music for the celebrations at Wembley, though this was not a happy occasion for him. Had Alice not died in 1920, might his attitude have been different? | 1999 July | 11 | 2 | 89 to 96 |

| Herter, Joseph A | Elgar?s Polonia Op.76 | The Great War (1914 to 18) did not inspire many Polish composers to write music ?for the cause.? Among works by Ignacy Paderewski and Zygmunt Stojowski, Elgar?s fantasia on Polish national airs provided the most outstanding, dramatic and nobly patriotic musical gesture for the Polish cause during the First World War. | 1999 July | 11 | 2 | 97 to 109 |

| Moore, Jerrold Northrop | Obituary: The Lord Menuhin (1916 to 1999) | Menuhin?s playing style owed much to his work with Elgar. The long lines of Elgar?s conducting connected Menuhin to the greatest violin traditions, going back through Ysae and Joachim to Vivaldi and Corelli, who were so important to Elgar. | 1999 July | 11 | 2 | 110 to 111 |

| Elgar and the boy violinist: a batch of letters | This article originally appeared in The Daily Telegraph on 20 October 1934 and includes the text of letters from Elgar to Menuhin in 1932, as well as one from Menuhin to Elgar. | 1999 July | 11 | 3 | 111 to 115 | |

| Moore, Jerrold Northrop | The return of the dove to the ark: ?Enigma? Variations a century on. | The article is based on the text of the author?s A T Shaw Lecture given to the Elgar Society on 5 June 1999 at Great Malvern. The Variations announced a mature new presence, with roots in the private experience of the man himself, and at the same time anticipating the career that was to unfold over the next twenty years. It was and still is without a parallel anywhere in music. | 1999 November | 11 | 3 | 134 to 143 |

| Hecht, Roger | Elgar?s Sea Pictures: A short history, interpretation, and annotated discography. | Sea Pictures was written in the same year as the Enigma Variations. Though popular with audiences from its premire, it has long existed in the shadow of its illustrious predecessor, particularly in the minds of critics. Much of the criticism centres on the texts, but the work repays close analysis and, however one ranks Sea Pictures as poetry, it is a fine piece of music. The discography assesses 16 full recordings of the work, plus a few historical partial readings. | 1999 November | 11 | 3 | 144 to 179 |

| Hodgkins, Geoffrey | ?Oh! That Sheffield chorus?: King Olaf at the 1899 Sheffield Festival | The first Sheffield Festival took place on 13th to 14th October 1896. Its success was acknowledged to have been based on the outstanding choral singing. The 1899 Festival lasted three days and included Elgar?s King Olaf. The composer, who was conducting, wrote that ?the chorus is absolutely the finest in the world?. The press reports of the time convey the success of the performance and the work itself. | 1999 November | 11 | 3 | 180 to 187 |

| Fellowes-Jensen, Gillian | King Olaf Tryggvason and Sir Edward Elgar | King Olaf is the subject of one of Elgar's early major works. Elgar may have been attracted to the subject because of its possible Scandinavian roots, but this view is open to dispute. A more likely explanation was the fashion of deriving inspiration from Nordic epic literature. The example of Longfellow was influential, particularly as he was one of Elgar's favourite authors. Elgar used only a very small part of the saga of Olaf, who is mentioned in several reputable historical sources. | 2000 March | 11 | 4 | 202 to 218 |

| Boyle, Rory | Interpreting Elgar: A conductor?s thoughts | Most of Elgar's great choral works were written for specific choral festivals and the quality of performances they received varied. The chorus is crucial to virtually every scene in these works, which makes the music most rewarding to conduct and sing. The Apostles and The Kingdom contain moments of tremendous drama as well as sheer beauty, and The Dream of Gerontius is a work of genius that is much more demanding, but even more rewarding to perform. | 2000 March | 11 | 4 | 219 to 226 |

| Hooey, Charles A. | Singer, soldier: Remembering Charles Mott | Surveys the life of the English baritone Charles Mott (d.1918), who began his musical career as a chorister in Muswell Hill and went on to perform a wide range of roles at Covent Garden. | 2000 March | 11 | 4 | 227 to 236 |

| Mitchell, Kevin D. | Any friend of Elgar?s is a friend of mine: Barbirolli and Elgar | John Barbirolli's association with Elgar's music began at a young age and continued to the end of his life. He played under Elgar's baton in 1919 to 20 and was an early interpreter of the violoncello concerto. He began to conduct Elgar's music from the outset of his career and his work was praised by Elgar himself. Many performances and recordings of Elgar's music followed; they did not always receive positive reviews from those who disliked his emotional approach, but were acclaimed by many others. He succeeded in affirming Elgar's stature as a composer. | 2000 July | 11 | 5 | 250 to 269 |

| Young, Percy M. | Elgar and Cambridge | In 1900 Charles Villiers Stanford proposed Elgar for an honorary MusD at Cambridge. Elgar initially intended to refuse the honour, but he was persuaded to accept. Several Cambridge performances of Elgar's music were given during his lifetime, including The Apostles and The Kingdom. | 2000 July | 11 | 5 | 270 to 275 |

| Rushton, Julian | A devil of a fugue: Berlioz, Elgar and Introduction and allegro | Elgar's fugues in The Dream of Gerontius (Demons' chorus), The Kingdom, and the Introduction and allegro are analysed and compared to similar music by Berlioz and Liszt. It is possible that Elgar associated fugues largely with demonic music, a view prompted by his description of the Introduction and allegro passage as "a devil of a fugue". | 2000 July | 11 | 5 | 276 to 287 |

| Hooey, Charles A. | More on Mott... | Following an article on the baritone Charles Mott in the previous issue of this journal (RILM 2000 to 50527), further material has come to light, including a letter sent to Elgar from Mott four days before he was fatally wounded in battle. | 2000 July | 11 | 5 | 288 to 289 |

| Hodgkins, Geoffrey | The passionate pilgrimage of a soul: Elgar and Canon Temple Gairdner | William Henry Temple Gairdner was born in Ardrossan in 1873. Upon the completion of his studies at Oxford he became a missionary in Cairo. After obtaining a score of The Apostles in 1904 he developed an interest in Elgar's music and began a correspondence with him. They subsequently met and Gairdner attended some of Elgar's concerts when he visited England. A collection of Gairdner's writings was issued in 1930, two years after his death, and includes a chapter analysing Elgar's second symphony. A reproduction of the chapter is included. | 2000 November | 11 | 6 | 306 to 324 |

| Hecht, Roger | Overview: English symphonies | There is a view that English symphonies have not fared well in the U.S. Part of the reason may be the special character of English music. Comparisons are made between the styles of British and American conductors and recommendations are made for recordings of each of Elgar's symphonies. | 2000 November | 11 | 6 | 325 to 333 |

| Trott, Michael | Frank Bernard Greatwich (1906 to 2000) | An obituary for Frank Greatwich, who died in Malvern on 20 September 2000. A journalist by profession, he was a founding member of the Elgar Society, was instrumental in the formation of the London branch, and helped arrange for Elgar's commemorative plaque in Worcester and the memorial stone in Westminster Abbey. | 2000 November | 11 | 6 | 333 |

| Hodgkins, Geoffrey | Two rare Elgar photographs | Two rare Elgar photographs are reproduced. The first appears in Landon Ronald's book 'Myself and others; and shows Elgar with A.S.M. Hutchinson, Sir Ernest Hodder-Williams, Sir Frederic Cowen, and Sir Landon Ronald. The second, which has only recently come to light, was found in a frame containing a photo of Bevanhill Cottage, Bromsgrove. It was taken in 1928 on the occasion of Herbert Brewer's funeral and shows Elgar with Charles Lee Williams (Brewer's predecessor as organist of Gloucester Cathedral) and Theodore Hannam to Clark, a member of the Gloucester Three Choirs Executive Committee. | 2000 November | 11 | 6 | 334 to 335 |

| Elgar and the Cambridge doctorate | On 22 November 1900, Elgar received an honorary doctorate from Cambridge University. The Public Orator gave a speech in Latin, listing Elgar?s achievements. This is printed here, along with an English translation. | 2000 November | 11 | 6 | 336 to 337 | |

| Smith, Barry | Elgar and Warlock (Philip Heseltine) | Elgar and Warlock would seem, on the surface, to have little in common. There are, however, some similarities in character and in the mood of their music. Elgar made quite an impression on the young Heseltine, who did not lose his enthusiasm for Elgar?s music even after he discovered Delius. There are numerous references to Elgar in Heseltine?s journal 'The Sackbut' and he was a signatory in the protest against Edward Dent?s treatment of Elgar. The article contains the full texts of Heseltine?s published writings on Elgar. | 2001 March | 12 | 1 | 2 to 20 |

| Another rare Elgar photograph | Most people are familiar with the photograph taken at Abbey Road when Yehudi Menuhin recorded the Elgar violin concerto (1932). The reproduction shown here is rare because it shows more details of the orchestra and equipment. Also reproduced is a page from the French set of discs, including Elgar?s inscription for the Menuhin family. | 2001 March | 12 | 1 | 21 | |

| Maund, Philip | Elgar's brass band thing: The Severn suite - postscript | Following the acquisition of Elgar's autograph brass band score of the Severn suite, it is now possible to be clear about the key in which Elgar intended it to be published, as it had long been thought that the first printed edition was a tone lower than intended. Examination of the score also sheds light on Elgar's scoring methods. | 2001 March | 12 | 1 | 24 to 29 |

| Denison, John | Playing with Elgar | John Denison was a horn player during the 1930s. As a freelance member of the Eastbourne orchestra he took part in an all-Elgar programme conducted by the composer. He recalls the passages Elgar rehearsed and describes the concert as being an inspiring occasion. | 2001 March | 12 | 1 | 29 to 30 |

| Mitchell, Kevin D. | A discography of Barbirolli?s Elgar recordings | John Barbirolli made many Elgar recordings between 1927 and 1970. The short reviews contain the original record numbers and the latest CD numbers at the time of writing. There is a list of comparative timings for different recordings of the major works. | 2001 March | 12 | 1 | 31 to 49 |

| Suter, Anthony | Nimrod in the metro: Hearing Elgar in France | Hearing Nimrod being played in the Toulouse metro prompted an investigation of Elgar's reputation in France. A study of Elgar performances on French radio was discouraging and some performances were disappointing. Coverage of CD releases during the last decade has been quite extensive, but historical reissues are rare. Conducting this study led to an examination of the author?s relationship with Elgar?s music: the idea that only English musicians can interpret Elgar properly is absurd, but listening to the music is still associated with a love of England. | 2001 July | 12 | 2 | 62 to 70 |

| Moore, Ruth Newcomb | Memoirs of a young singer | Ruth Newcomb Moore (nee Price) was born in 1914. As a member of the Croydon Philharmonic Society Choir from 1934 to 1943 she took part in many Elgar performances. Diary entries form the basis of these memoirs, which recall rehearsals and performances featuring many famous singers of the day, including Isobel Baillie and Heddle Nash. | 2001 July | 12 | 2 | 71 to 85 |

| Clegg, Nora | Edward Elgar | The author was the sister-in-law of the Rev. Charles Gorton, a friend of Elgar's. She wrote an article on Elgar and his choral music for her music society, incorporating information from published works and anecdotes provided by Gorton. | 2001 July | 12 | 2 | 86 to 90 |

| Whittle, John | A record life: 1927?1975 | This is the text of a speech given by John Whittle on the occasion of his retirement from EMI. From an early age, Whittle loved gramophone records. He began his career in 1925 with a holiday job at the HMV shop in Oxford Street, progressing to running the sales promotion department from 1947 and becoming a senior executive in the classical department. He was involved with many great recordings and artists, and has fond memories of working with the regional orchestras. His proudest achievement was the recording of Elgar's The Apostles. | 2001 November | 12 | 3 | 106 to 117 |

| McVeagh, Diana | Elgar's Concert allegro | In 1901, the pianist Fanny Davies asked Elgar for a concerto. The new piece was performed in December 1901 but was not published. At the time of writing a MS had recently come to light; after analysing the MS, the author and John Ogdon independently concluded that this was Fanny Davies' copy of the Concert allegro. Ogdon performed the work on television in 1969, the first performance in 60 years. (Reprint of an article from 1969) | 2001 November | 12 | 3 | 118 to 124 |

| Zimmermann, Frank-Peter | Elgar Violin Concerto | Frank-Peter Zimmermann was interviewed for Bavarian Radio on 9 March 2001 and spoke about the concerto. Having performed it several times, he believes it to be a great virtuoso work, with mystical moments, which reflects the mood of its time. | 2001 November | 12 | 3 | 124 to 126 |

| Suter, Anthony | Post-scriptum to Nimrod in the Metro | An addition to the article in 12/2 | 2001 November | 12 | 3 | 127 |

| Coronation ode: Analytical notes | Joseph Bennett (1831?1911) was one of the leading music critics of his day. This analysis was written, by special request, for a state performance of Elgar?s Coronation ode in Covent Garden Theatre, to celebrate what should have been the coronation of Edward VII. The king?s illness resulted in the cancellation of the performance, but the work is valuable in its own right. The analysis is followed by a letter from Elgar to Herbert Thompson explaining the ideas behind the work. | 2002 March | 12 | 4 | 138 to 155 | |

| Herter, Joseph A. | Elgar's Polonia updated | Information concerning Elgar's Polonia can now be updated following the discovery of additional programmes and newspaper clippings. The first American performance took place as part of a benefit concert in 1916 for Paderewski's Polish Victims Relief Fund; the programme included music by Wieniawski, Paderewski, Chopin, and Moniuszko. The reviews show that Polonia was well received. | 2002 March | 12 | 4 | 156 to 159 |

| Langford, Samuel; Priestley, J.B.; Cohen, Alex | Elgar and Englishness | Three articles, previously published in other forms, explore the view of Elgar as an Englishman and an Edwardian. Although his music is appreciated in other countries, it changed the face of music in England, particularly in the development of choral singing. In spite of the generally accepted Englishness of his music, he should not be seen as insular and it cannot be assumed that the best interpreters are always English. | 2002 March | 12 | 4 | 160 to 166 |

| Lemon, David | Elgar's Gerontius: A dream of transcendence | The imagery in The Dream of Gerontius occasionally proves an obstacle to the appreciation of the work. It is rooted, however, in English literature and art, and should be seen in the context of the works of Blake, Donne and Turner. When Elgar was writing the work, audiences would have been familiar with the themes of death, transformation, and redemption. An analysis of the work with these thoughts in mind enables the listener to make sense of the work and to accept the imagery in this unique oratorio. | 2002 July | 12 | 5 | 183 to 191 |

| Shiel, Alison I. | Charles Sanford Terry in the Elgar diaries: The chronicle of a friendship | Charles Sanford Terry, one of the leading music scholars of his day, developed friendships with many eminent musicians, including Edward Elgar. This friendship was at its peak from 1906 to 1920 and included Sir Edward, Lady Elgar, and their daughter Carice. The bond between Terry and Carice is particularly touching and is illustrated by mementoes in the Elgar Birthplace Museum. Terry was able to support the family in troubled times and was also present at important musical occasions. It can be said that Terry's interest in Bach was inspired by his friendship with Elgar and Ivor Atkins. | 2002 July | 12 | 5 | 192 to 201 |

| Foreman, Lewis | Sir Charles Villiers Stanford (1852 to 1924): Choral music - A personal odyssey for the 150th anniversary of his birth | Stanford has long been recognized as a composition teacher, but only now is he beginning to be seen as an important figure in British music. His temperament often led to disputes with his contemporaries, but he was always able to recognize worthwhile music. He was a prolific composer in most forms of music, but only his choral music gained immediate recognition. Discovering lesser to known choral masterpieces has been made more difficult by publishers disposing of performance material and by changes in personnel. His later works show a composer out of his time, but there are examples which are worth reviving, a case in point being Merlin and the Gleam, currently being re to orchestrated for performance by the Broadheath Singers. | 2002 July | 12 | 5 | 202 to 208 |

| Walker, Arthur D. | Symphony no. 1: A paper trail to its past | A hand-dated miniature score of Elgar?s first symphony appeared initially to be a first issue. Study of another score cast doubt on this assumption, and offers clues to the timing of the work?s early performances under Richter and Elgar. | 2002 July | 12 | 5 | 209 to 210 |

| Johnson, Stephen | Elgar-Payne: Whose symphony? | Anthony Payne's elaboration of the sketches for Elgar's third symphony is a musical success. Had Elgar completed the work himself, the result would have been different, but it is now impossible to look at Elgar's sketches without understanding them within the context created by Payne. On the surface the work appears to be the product of two creative minds, but there are many subtleties which point to a unifying purpose. Payne has said that much of his work was not the result of conscious calculation, but that ideas and developments seemed to suggest themselves. The end result is one integrated, compelling work, in which the honours are equally divided. | 2002 November | 12 | 6 | 235 to 242 |

| Bury, David | Was Arthur Benson a jingoist? | The words of Land of hope and glory attract the charge of jingoism. Whilst Elgar has been largely exonerated, the case for the author of the words, Arthur C. Benson, needs to be explored. There is no evidence that Elgar disliked the words, which met the needs of the time. Benson was neither a man of strong political views nor a royal sycophant, and he deplored the Boer War. He was a prolific poet with real talent, was kind, generous, and tolerant, and hated bombast and cruelty. He should not be condemned on the grounds of some of the words in his most famous poem. | 2002 November | 12 | 6 | 243 to 251 |

| Shiel, Alison I. | Charles Sanford Terry and the Elgar violin concerto | Elgar's violin concerto, and the circumstances surrounding its composition, has been the subject of much scholarly activity. Additional light has been shed on the work by the study of a volume in the British Library, London, consisting of a first-proof copy of the score (given to Terry by Elgar) along with letters from the Elgars, notes and observations by Terry, and concert tickets. The notes show that Terry was closely involved with the early rehearsals and performances, although he makes no reference to any private history which may lie behind the dedication or the music. | 2002 November | 12 | 6 | 252 to 261 |

| Reynolds, Arthur S. | Hedley's Elgar | An inscription on Percival Hedley's bronze bust of Elgar in the National Portrait Gallery prompted comparison with a similar wax version. Researching the links between the two brought to light information on the sculptor?s main work as a prolific medallist. He produced a series of plaques showing portraits of musicians of his day including Saint-Sans, Hans Richter, Clara Butt, and Tchaikovsky. | 2003 March | 13 | 1 | 3 to 9 |

| Hooey, Charles A. | Muriel the gorgeous | The contralto Muriel Foster (1877?1937) was a friend of Elgar and his preferred performer in many of his works, some of which were written with her in mind. From her time as a student at the Royal College of Music, she decided to avoid opera and concentrate on oratorio and recitals. In addition to regular work in England, she performed in Germany, Holland, Russia, Canada, and the U.S., always to great critical acclaim. Sadly, she made no recordings, but should be remembered for her contribution to Elgar's music in particular. | 2003 March | 13 | 1 | 10 to 25 |

| Gould, Corissa | Edward Elgar, the Crown of India, and the image of empire | Elgar's music for Crown of India was written in 1912 in response to a commission for a masque at the London Coliseum. Its artistic integrity has been questioned over the years by commentators who are uncomfortable with its imperialist sentiments. A re-examination of the text and music provides a starting point for a more historically accurate view. | 2003 March | 13 | 1 | 25 to 35 |

| Shiel, Alison I. | Elgar's visits to Aberdeen | Elgar's friend, Charles Sanford Terry, was professor of history at Aberdeen University. Terry invited Elgar to Aberdeen in 1906 to receive the degree of honorary LLD and to encourage local musicians. In 1909, Elgar was invited to a banquet in honour of Terry, where both spoke on the subject of municipal aid for musical events, and on the importance of audience education. In subsequent years Terry was to help Elgar with his violin concerto and with the Elgar-Atkins edition of Bach's St. Matthew Passion. | 2003 March | 13 | 1 | 36 to 40 |

| Moore, Jerrold Northrop | A word to the wise | The break up and sale of the Novello archive has been the subject of recent discussion. Jerrold Moore, during his preparation of much Elgar correspondence for publication, put routine letters concerning Elgar's conducting engagements to one side. These unpublished letters, which are the subject of the discussion, are not in the same league as the published correspondence. | 2003 July | 13 | 2 | 3 to 4 |

| Parrott, Ian | Elgar: "The first English progressive musician" | The Apostles is arguably Elgar's greatest choral work. The music is bold and forward-looking, with original orchestration, and is astonishingly modern in comparison with the preceding era of Victorian hymns. | 2003 July | 13 | 2 | 5 to 8 |

| Hodgkins, Geoffrey | Everything I can lay my hands on: Elgar?s theological library. I | Elgar assembled his own libretto for The Apostles. His tuition in the Catholic faith had been largely based on verbal communication, so his knowledge of the Bible was, at first, limited. The wide variety of sources which he consulted can be identified by those volumes which remain in the Elgar Birthplace collection and from the 1918 inventory of the contents of Elgar's London home, Severn House. (Part II appears in 14/5) | 2003 July | 13 | 2 | 9 to 18 |

| Hooey, Charles A. | The immortal sextet | The Apostles calls for six soloists. At the first performance these were Emma Albani, Muriel Foster, John Coates, Robert Kennerley Rumford, David Ffrangcon-Davies, and Andrew Black. Each of these was an established soloist. All except Foster and Ffrangcon-Davies can be heard on record. | 2003 July | 13 | 2 | 19 to 26 |

| Smith, Richard | "Shophar, sho good": Early American performances of 'The Apostles' | The first performance of The Apostles in the U.S. took place in New York in February 1904. The work was coolly received but earned much better reviews after the second performance several weeks later. Subsequent performances included two conducted by Elgar himself in 1906 and 1907. | 2003 July | 13 | 2 | 27 to 36 |

| Staveley, Norman | A provincial performance of The Apostles | The first performance of The Apostles in Kingston upon Hull took place in March 1907. A public lecture on the work was given during February by Dr Thomas Keighley, who illustrated the leitmotifs at the piano. The performance was well received but since then the work has only been performed on one further occasion, in 1938. | 2003 July | 13 | 2 | 37 to 39 |

| McCann, Wesley | Early performances of Elgar's music in Belfast | Elgar's only visit to Ireland took place on 21 October 1932 to conduct the Enigma variations and The Dream of Gerontius in Belfast. Music making in Belfast was largely based on several amateur choral societies; the most significant of these was the Belfast Philharmonic Society, whose concerts attracted many international soloists. A local impresario, H.B. Phillips, promoted ambitious concert series throughout Ireland, and the BBC opened its Belfast station and formed a permanent orchestra in 1924. Audiences were therefore able to enjoy a wide range of music, including many performances of music by Elgar by leading interpreters. | 2003 November | 13 | 3 | 3 to 14 |

| Hawker, Nicholas | Composer as librettist: Elgar's notes on The Apostles | In comparison with The Dream of Gerontius, the libretto of The Apostles has been subject to much criticism of its supposed lack of a central focus. Elgar may have been aware of this possible interpretation and compiled a series of notes, mainly concerned with his compilation of the libretto. These notes, now in the British Library, London, show that he was primarily concerned with portraying characters, particularly Judas Iscariot. They provide a fascinating insight into the changes he made, the sources he consulted and his use of various authentic musical themes, and show that the work should be seen as a carefully written whole. | 2003 November | 13 | 3 | 15 to 27 |

| Kelly, John | Alfred Edward Rodewald (1862?1903) | Alfred Edward Rodewald was born on 28 January 1862. He learned piano and violin as a boy, then moved to double bass while at Charterhouse. He took over the running of the family cotton brokerage in Liverpool in 1892, and became well known in musical circles, conducting the Liverpool Orchestral Society and introducing much previously unfamiliar music, such as Wagner's. He was friendly with many musicians and formed a particularly close friendship with Elgar. A sudden illness led to his death in 1903, leaving Elgar distraught. It is usually forgotten that the famous Pomp and circumstance march no.1 was dedicated to Rodewald and his orchestra: surely a fitting memorial. | 2003 November | 13 | 3 | 29 to 35 |

| Hodgkins, Geoffrey | Watchmen - but what of the Knight? Elgar and the musical press | In 2002, Meirion Hughes published a view of Elgar as a skilled manipulator of the musical press. This is a misrepresentation, shown here by looking at the background to the cuttings books, 15 volumes of press cuttings (clippings), which are kept at the Elgar Birthplace Museum in Broadheath. The assertion that Elgar had good relationships with several critics is not borne out by the facts: he was much more interested in working musicians. He was certainly not praised by much of the musical press and, in turn, made less than complimentary remarks about critics in general. The conclusion is that Hughes's case is conjectural and that Elgar's reputation rests on his music rather than on its reception by critics. | 2003 November | 13 | 3 | 36 to 43 |

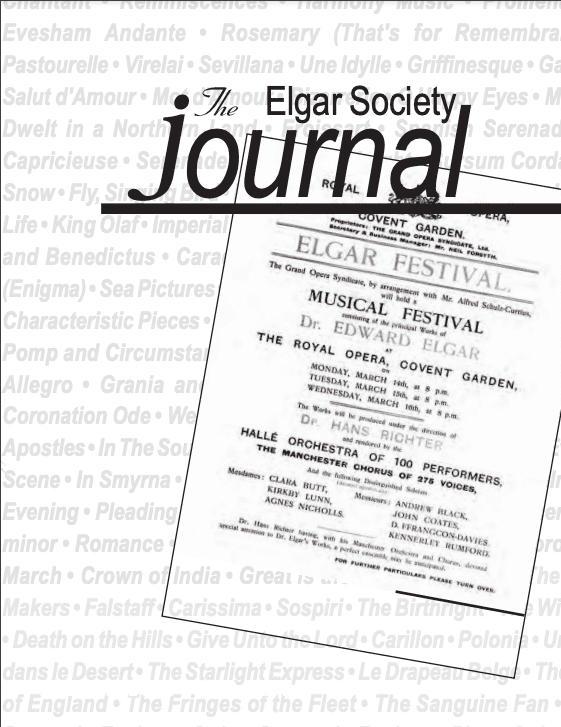

| Reynolds, Arthur S. | The Elgar Festival at Covent Garden - March 1904 | The idea of an Elgar Festival was proposed by Frank Schuster in 1903. The three day festival was remarkable both for the length of time devoted to one composer and for the fact that it did not take place in one of the London concert halls. It therefore attracted a new audience from smart society; the king and queen unexpectedly attended on the second night as well as the first. The festival was a huge success and led to Elgar being knighted. Perhaps, however, it also resulted in his losing touch with his younger self as he tried to cope with fame. | 2004 March | 13 | 4 | 3 to 14 |

| Harper-Scott, J.P.E. | Henry and the Grfin/grinder: Elgar and The Starlight Express | The Starlight Express, op. 78, was a stage adaptation by Violet Pearn of the Algernon Blackwood novel, A Prisoner in Fairyland. Elgar's incidental music for the play was written in 1915, at a time of national and personal artistic crisis and has generally been regarded as escapist fantasy. But an examination of the themes of the novel, and their changed appearance in the play, suggests that Elgar's interest in the project might be explained by darker aspects of what seems ostensibly a whimsical story of childhood adventure. Seen in this light, the work begins to resonate with other, better known works by Elgar which deal with childhood in similarly surprising ways. | 2004 March | 13 | 4 | 15 to 23 |

| Trott, Michael | Elgar's remarkable mother | Ann Greening was born in 1822 in Herefordshire. She grew up in a family of farm labourers with few opportunities for education, but became a voracious reader of books and poetry. She married William Elgar in 1848 and had seven children, one of whom was Edward. He inherited her love of literature and the countryside; she surely had a significant influence on his development as a composer. | 2004 March | 13 | 4 | 25 to 28 |

| Lace, Ian | Bernard Herrmann's admiration and appreciation of Elgar | Bernard Herrmann, best remembered for his film scores, was a keen Anglophile, visiting England on many occasions and living there towards the end of his life. In his youth he championed Elgar's music in the U.S., conducting Falstaff as well as the more popular pieces. In 1957 he wrote a short essay for Novello on an American?s impression of Elgar?s music. He believed that few conductors outside England appreciated the flexibility of tempo required for a successful performance. | 2004 March | 13 | 4 | 29 to 33 |

| Shiel, Alison I. | Elgar, Charles Sanford Terry, and J.S. Bach | The music of Bach was important to Terry and Elgar from their childhood, although their early lives followed quite different paths. Their own friendship developed through their involvement in the Three Choirs Festival. Terry was influential in the preparation of the Elgar-Atkins edition of the St. Matthew Passion, an edition which he used in his Bach Society concerts in Aberdeen. The music of Bach continued to be of great importance to both Terry and Elgar throughout their lives: for Terry as a Bach scholar of worldwide fame, and for Elgar as an influence in composition. | 2004 July | 13 | 5 | 3 to 12 |

| Ward, Yvonne M. | Edward Elgar, A.C. Benson, and the creation of Land of hope and glory | Elgar has frequently been criticized for writing imperialist music and Arthur Benson derided as a minor jingoistic poet. Together they produced what has become a second national anthem, the writing of which is surrounded by myth and legend. The first version was written as the finale to a Coronation ode, op. 44, planned for the coronation of King Edward VII; the second was written as a popular song for the coronation concert. They survive as two separate musical works. | 2004 July | 13 | 5 | 13 to 25 |

| Moody, Catherine | The sounds that Elgar heard. I: A background for composition - Saetermo and Forli | Elgar was extremely sensitive to his surroundings and to nature. The same surroundings have provided the author with inspiration for creating paintings. The sounds he would have heard and the views he would have seen from two of his houses, Saetermo and Forli, were still there years later to influence a new generation of artists. (Part II appears in 13/6) | 2004 July | 13 | 5 | 27 to 35 |

| Parkin, Ernest | Elgar and literature | Elgar?s love of literature was nurtured by his mother, who particularly loved the works of Longfellow. Elgar was a model of self education; he read widely and his reading influenced his music. He used literature for the purpose of self-revelation and self-concealment, communicating his feeling about his art through literary texts and allusions. | 2004 November | 13 | 6 | 3 to 22 |

| Moody, Catherine | The sounds that Elgar heard. II: A composer, nature and the human condition | Birchwood Lodge was a cottage used by the Elgars as a retreat for several years. Although not far from Malvern, it provided relief from teaching and the class structure of Malvern society; it was here he learned to ride a bicycle. (Part I appears in 13/5) | 2004 November | 13 | 6 | 23 to 30 |

| Moodie, Andrew | Elgar?s "Enigma": The solution? | During his life Elgar hinted at the source of the "Enigma" theme. These could possibly have been red herrings designed to hide the fact that the theme is based on the letters of Alice Elgar's name in the form of Carice. | 2004 November | 13 | 6 | 31 to 34 |

| Green, Edmund M. | Elgar?s "Enigma": A Shakespearian solution | Many people have attempted to solve the mystery of the "Enigma" theme, but no one has, as yet, suggested a purely literary solution. The larger theme referred to by Elgar is Shakespeare?s 66th sonnet, whose lines tie in with the idiosyncrasies of his friends, and the word "Enigma" stands for the real name of the dark lady in sonnets 127 to 152. | 2004 November | 13 | 6 | 35 to 40 |

| Pickett, Stephen | Elgar?s "Enigma": A decryption? | Many people have struggled to find the larger theme in the Enigma variations. Far from being a musical theme, the solution is an acrostic linking the names or initials of the variations with the title, Rule Britannia. | 2004 November | 13 | 6 | 41 to 45 |

| Moody, Catherine | The sounds that Elgar heard. III: The human life and nature in balance | Before her marriage to Elgar, Alice Roberts lived in Redmarley d?Abitot among a society interested in research in the natural sciences. This social life prepared her for the role she was to play in supporting Elgar as he became well known. Another family connected with Elgar, the Norburys, lived at Sherridge in Leigh Sinton. Winifred Norbury assisted him with writing orchestral parts and Florence was responsible for introducing Elgar's music to Richter in Germany. (Parts I and II appear in 13/5 and 13/6) | 2005 March | 14 | 1 | 42341 |

| Reynolds. Arthur S. | The last later-Romantics: Edward Elgar and John Singer Sargent | Elgar and John Singer Sargent met on a few occasions at the house of Frank Schuster. Their mutual respect never became friendship but they had more in common than this acquaintance might suggest. Their respective childhoods did not augur well for future greatness, in spite of having talented fathers. Both mothers fostered a love of Romanticism and neither boy had what could be called a formal education. Sargent loved music and both men were influenced by Wagner. One of the reasons why they did not become better acquainted may be that, by the time they met, Elgar was well established and did not need the kind of support which Sargent provided for Faur, Albniz, and other musicians. | 2005 March | 14 | 1 | 13 to 30 |

| Elgar, Edward | The College Hall | College Hall is part of the King's School in Worcester. It was used for concerts at which many great musicians appeared and Elgar's father played in the orchestra there. In 1881 Alexander Mackenzie's The Bride was performed, a great event for young musicians to witness. Elgar met Mackenzie on that and subsequent occasions and paid tribute to him in this short article. | 2005 March | 14 | 1 | 33 to 35 |

| Parrott, Ian | The seeds of greatness | On first hearing, some of Elgar's early music may seem bland. There are, however, signs of his future mature style in earlier works, in particular the organ sonata op. 28. Slow movements develop so that the second subject is often more impassioned as Elgar's inspiration increases. | 2005 March | 14 | 1 | 36 to 38 |

| Pickard, John | Disillusion and dissolution: Elgar and the poetry of doubt | Elgar's music is believed by some to be arrogant and jingoistic. Detailed study of the music, particularly the symphonies, concertos, and chamber music, shows that behind the mask are deep emotional truths and a thorough knowledge of the techniques of the Classical masters. | 2005 July | 14 | 2 | 3 to 17 |

| Blamires, Ernest | "Loveliest, brightest, best": A reappraisal of Enigma's variation XIII. I | The subject of Elgar's variation 13 from the Enigma variations has long been thought to be Lady Mary Lygon. This view is supported by some of Elgar's notes, but study of other sources suggests a closer link with the fiance of Elgar's youth, Helen Weaver. | 2005 July | 14 | 2 | 19 to 36 |

| Moody, Catherine | Elgar at the wheel | A photograph in a previous edition of the Elgar Society Journal shows Elgar at the wheel of an unidentified car. Investigation into the likely model of this car provides information on the early days of car manufacture and motoring in the Malvern area. It is possible that the mystery car is a Burston steam-car. | 2005 July | 14 | 2 | 37 to 46 |

| Andrew Neill | Elgar in Smyrna, 1905 | In September 1905 Elgar embarked on a month's cruise in the eastern Mediterranean, visiting Greece and Turkey, as a guest of the Royal Navy. Photographs and excerpts from his journal convey his impressions and experiences and provide information on the people who accompanied him. It is also possible to gain an insight into continental travel 100 years ago. The voyage resulted in the composition of the piano piece In Smyrna. | 2005 November | 14 | 3 | 3 to 24 |

| Blamires, Ernest | "Loveliest, brightest, best": A reappraisal of Enigma's variation XIII. II | In 1899, Lady Mary Lygon was told by a friend that Elgar had portrayed her in his new Variations on an original theme, ("Enigma"). In order to avoid naming Variation 13, Elgar inserted three asterisks, masking the identity of the real dedicatee, Helen Weaver, and allowing people to believe that the asterisks indicated Lady Mary. Subsequent letters and information provided by Wulstan Atkins support this theory. (Part I appears in 14/2) | 2005 November | 14 | 3 | 25 to 37 |

| Bird, Martin and Blamires, Ernest | The Shover uncovered | Identifies a car driven by Elgar using photographs and entries in the Elgar diaries. The car, believed to be a Panhard et Lavassor, belonged to Alfred Rodewald and was nicknamed "The Shover" by Rodewald and August Jaeger. | 2005 November | 14 | 3 | 39 to 44 |

| Hodgkins, Geoffrey | The boon of far Peru | In 1903, Elgar asked August Jaeger to send a postcard to Alfred Rodewald with the question: ?What is the boon of far Peru?? It is unclear whether the source of the quote is a poem by Richard Barham (Thomas Ingoldsby) or the musical play The orchid, by Lionel Monckton. | 2005 November | 14 | 3 | 45 to 47 |

| Green, Edward | Sir Edward Elgar, master of rhythm | The music of Elgar receives an increasing amount of scholarly respect. His mastery of rhythm, however, is less widely appreciated. Analysis of his music, in particular the first symphony and Pomp and circumstance march no.1, reveals rhythmic drama and subtle syncopation which contribute greatly to the excitement of the music. Elgar was able to bring opposites together and to use unusual time signatures to great effect. A prime example of his rhythmic imagination can be found in the Angel?s Farewell from The Dream of Gerontius. | 2006 March | 14 | 4 | 42125 |

| Moody, Catherine | The sounds that Elgar heard. V [sic]: Elgar, Troyte Griffith and the geology of Malvern | Previous articles have shown how Elgar?s surroundings can be seen as a setting for his musical progress. Some of the correspondence between Elgar and Troyte Griffith gives clues to his interest in the geology of the Malvern area. Alice Elgar is known to have been interested in the subject and could well have passed on her enthusiasm to her husband. | 2006 March | 14 | 4 | 17 to 27 |

| Neill, Andrew | Elgar in Smyrna, 1905: An addendum | Following a recent visit to Istanbul, it is clear that, in spite of its great increase in size, the city and its surroundings would still be recognizable to a visitor of a century ago. The Turkish ambassador to Britain, during a visit to the Birthplace, noted that the piano piece In Smyrna conveyed the feeling of Izmir in the 1950s. The quiet atmosphere is at the centre of the memories which Elgar expressed in this piece. (Commentary on the article in 14/3) | 2006 March | 14 | 4 | 28 to 29 |

| Plant, Michael | In memoriam: The Record Guide (1951 ? 56) | Although the final part of this valuable work is fifty years old, the reviews remain useful and interesting. The authors? treatment of Elgar is of great interest from today?s perspective, particularly their discussion of the cello concerto long before it became a world-wide best seller. | 2006 March | 14 | 4 | 30 to 31 |

| Hollingsworth, Norma E. | I believe in angels: The role and gender of the angels in The Dream of Gerontius | The belief in angels was absorbed by the early tribes of Israel from surrounding nations and was inherited by the Christian faith. In order to describe spirit beings, they began to be pictured in human form. In writing The Dream of Gerontius, Newman assumed his angels to be male, in line with the theological thinking of the times. Elgar?s angels, however, are both male and female, for practical musical reasons and in order to depict the character of the angels. The music of the Guardian Angel is tender and gentle, therefore womanly. In this work, Elgar took the courageous step of moving away from the stereotypical masculine image of angels. | 2006 July | 14 | 5 | 5 to 13 |

| Smith, Richard | Elgar, Dot and the Stroud connection (Part 1) | Stroud in Gloucestershire has a connection with Elgar through his sister, Helen Agnes, known to the family as Dot. A retiring child, Dot wanted to become a nun from an early age, but stayed at home to look after her mother. She also became book keeper for the Elgar music shop. In 1902 she entered St. Rose?s Convent in Stroud. Her correspondence with Elgar continued throughout the rest of his life. She held several offices there, including that of Music Mistress, and in 1919 was appointed Mother General of the five linked convents of St. Rose. Following a serious illness, she was relieved of these duties in 1925, and continued in devoted service until her death in 1939. | 2006 July | 14 | 5 | 14 to 20 |

| Hodgkins, Geoffrey | Everything I can lay my hands on: Elgar's theological library. II | By the time of the first performance of The Apostles, Elgar had already done a great deal of work on what was to become The Kingdom. As before, he consulted a wide variety of books to assist his compilation of the libretto from many passages in scripture. Some of the books in his library also show that he had begun working on the unfinished third oratorio The Last Judgement. The scope of his collection shows that we can count theology as one of Elgar?s many interests, although his known impatience with organized religion means that we cannot assume agreement with the views expressed in the books. | 2006 July | 14 | 5 | 5 to 13 |

| Smith, Richard | Elgar, Dot and the Stroud connection (Part 2) | A continuation of the article in 14/5. | 2006 November | 14 | 6 | 5 to 13 |

| Rushton, Julian | The A.T. Shaw lecture, 2006: Elgar, Kingdom, and empire | The German title of The Kingdom is Das Reich, a word usually translated as "Empire". Discussion of the different meanings of these words gives rise to thoughts about Elgar?s oratorios. In the music, the Kingdom of God is seen as being on earth and the compositions reflect Elgar?s changes in attitude towards religion and his resignation in looking to the future. | 2006 November | 14 | 6 | 15 to 26 |

| Bennett, Sylvia | The enigma of a variation: The story of the "Dorabella bequest". I: The Sheffield Elgar Society and the Royal College of Music | The Sheffield and District Elgar Society existed from 1950 until 1983. In 1952 Carice Elgar Blake was president and Dora Powell one of the vice presidents. When "Dorabella" died in 1962, she left a collection of Elgarian materials to the Society. More recently, the location of the bequest was unknown. Research in the Sheffield Archive showed that the material, possibly somewhat depleted, was now at the Royal College of Music, as Dorabella had wished. The collection includes diaries, proof copies of some Elgar works, and the manuscript of The shepherd?s song. The inscriptions and dedication are puzzling. (Part II appears in 15/1) | 2006 November | 14 | 6 | 27 to 32 |

| Newbould, Brian | Elgar and "his ideal", Schumann | Elgar is known to have admired Schumann. Study of each composer?s piano quintets, in particular, shows signs of a strong influence, which is backed up by biographical information. | 2006 November | 14 | 6 | 33 to 40 |

| Plant, Michael | A view of Elgar from the past: The Edwardians, by J.B. Priestley | In 1970, towards the end of Priestley?s career, he published an illustrated book entitled The Edwardians. It is a useful account of life in England when Elgar?s powers were at their peak. It includes coverage of political reform, women?s suffrage, the loss of the Titanic, the Great War, as well as music and theatre. His admiration for Elgar shows in his perceptive comments about the music and Elgar?s contemporaries. | 2006 November | 14 | 6 | 41 to 43 |

| Blunnie, Roisin | A high-Victorian spyglass: Scenes from the saga of King Olaf and late nineteenth century British idealism | Longfellow?s Saga of King Olaf contains 22 episodes and required considerable abridgement to turn it into a manageable libretto. Harry Arbuthnot Acworth worked with Elgar but it is difficult to know how much influence he had in the editing process. Some material was considered unsuitable for audiences and was left out completely, resulting in the sanitisation of Olaf himself; other scenes were re-written. The result is a piece which reflects the prevailing attitudes of the time. Musically and as an historical document it is a work of great worth. | 2007 March | 15 | 1 | 5 to 14 |

| Norris, David Owen | The seas of separation: The mythic archetype behind Elgar's songs, with a performer's analysis of Sea pictures | There are several theories concerning the emotional roots of Elgar?s songs. His concern with the hidden meaning explains his habit of changing the original words. Elgarians may be too ready to believe that his music reflects incidents in his life, but studying Sea pictures gives rise to the theory that the songs are connected with Helen Weaver, his lost love. | 2007 March | 15 | 1 | 15 to 30 |

| Bennett, Sylvia | Touching snow: The story of the "Dorabella bequest". II: The riddle of The shepherd's song | The Dorabella bequest held at the Royal College of Music contains the MS of The shepherd?s song. The dedication is puzzling, as it has been heavily crossed out. Research shows that the song was dedicated to Mary Frances Baker, a friend of the Elgar?s who later married Dora Penny?s father. It is possible that "Minnie" Baker crossed out the dedication herself, in an effort to conceal details of her friendship with Elgar. | 2007 March | 15 | 1 | 31 to 37 |

| Jones, Patrick | From the desk of a cellist: Symphony no. 2 | Elgar?s second symphony is not undertaken lightly by an amateur orchestra, so the Manchester Beethoven Orchestra?s rehearsals provided valuable opportunities to learn the music thoroughly. After initial doubts, the final movement, in particular, reconciled the orchestra to this music and enabled the musicians to enjoy playing it. | 2007 March | 15 | 1 | 39 to 42 |

| Plant, Michael | In search of Fritz Kreisler | The career of Fritz Kreisler is of interest to Elgarians as he was the dedicatee of the violin concerto. Unfortunately he recorded none of Elgar?s music. He was a child prodigy and, after beginning medical studies, became a traveling virtuoso. He settled permanently in America in 1939. One wonders how good a recording of the violin concerto he might have made, given his age and technical abilities at the time when this might have been possible. He has, however, left a marvellous legacy of recordings and will be remembered for as long as fine violin playing is valued. | 2007 March | 15 | 1 | 43 to 46 |

| The Gerontius panels in Westminster Cathedral | Argues that two marble panels flanking the Chapel of the Holy Souls at the Westminster Cathedral relate to The Dream of Gerontius. The left-hand panel celebrates Gerontius, whose story reflects the upward surge of the purified soul from Purgatory to Heaven. The right-hand panel links the stave with the cross and with a ladder symbolising the soul?s ascent, thus making an anagogical equivalent of The Dream. Where elements intersect, a point of light represents, so to speak, a spiritual spark. The route upward, via the ladder (perseverance) and the stave (art), produces a number of these flashes of illumination; but the route of greatest illumination is through the ladder, stave, and cross together, i.e. Perseverance, Art and Faith. | 2007 July | 15 | 2 | 5 | |

| McBrien, David | A visit to "The Hut" | Elgar was a frequent visitor to this house in Bray, Berkshire and frequently used the detached music room. The house and its surroundings are now very different to those days in which the house was owned by Frank Schuster. In 1926 the name was changed to "The long white cloud" by its New Zealander tenant. Later the house was the childhood home of Stirling Moss. The music room has been demolished and seven houses now stand on the original plot. Very few photos exist showing Elgar at "The Hut" but three have appeared in published works. (Additional information concerning the photographs appears in November 2007, 15/3) | 2007 July | 15 | 2 | 7 to 18 |

| Gleaves, Ian Beresford | Elgar and Wagner | Elgar was one of many composers influenced by Wagner. One important similarity between the two is that they were both largely self taught; another is that they were both complete masters of harmony and orchestration. In spite of Elgar?s documented admiration for Wagner, he managed to retain his own individuality, although there are instances where the influence can be heard. | 2007 July | 15 | 2 | 19 to 26 |

| Reynolds, Arthur S. | Elgar and Joachim | The violinist Joseph Joachim accumulated many accolades during his life. Elgar and Joachim were both frequent guests at Edward and Antonia Speyer?s house parties. Elgar gave to his niece, May Grafton, a discarded string from Joachim?s violin, describing it as "a precious relic". Elgar was believed by his violin teacher to have the makings of a very good violinist, but after hearing Joachim play Elgar decided his own tone was inadequate. Joachim, venerated as a performer, was also revered as the last great musician of the German Romantic style. He was primarily responsible for bringing this style to Britain, thereby influencing the music of Elgar and others of his generation. | 2007 July | 15 | 2 | 27 to 52 |

| Hodgkins, Geoffrey | The BBC and the Elgar centenary | A composer?s reputation is often at its lowest around the time of the centenary of his birth. In 1957 the centenary was largely marked by BBC radio, with talks and concerts including The Kingdom, which had fallen into neglect. Many major and some lesser known pieces were performed during May and June; given the reputation of Elgar at the time, the coverage was extremely generous. | 2007 July | 15 | 2 | 53 to 57 |

| Ghuman, Nalini | The third "E": Elgar and Englishness | Elgar?s music has long been seen as expressing "Englishness". This has prevented it from being played abroad, except for individual efforts by a small number of musicians. This nationalistic rhetoric must be abandoned if the music is to take its rightful place in the international repertoire. | 2007 November | 15 | 3 | 5 to 12 |

| Lyle, Andrew | When I was at the lunatic asylum...: Elgar at Powick 1879?1884 | Powick Lunatic Asylum was notable for its humane regime, including the provision of music and dancing. Close examination of the records reveals details of the entertainments and activities. Elgar was engaged at Powick for six years, conducting the band and composing music. Additional sketches have recently come to light, causing one to wonder how much more may have been lost. Future publication in the Elgar Complete Edition will show how these compositions helped Elgar develop as a composer. | 2007 November | 15 | 3 | 13 to 28 |

| Hooey, Charles A. | Clarity for Muriel | Since the publication of the article about Muriel Foster in the Elgar Society Journal 13/1 (Mar 2003), new information has been provided, filling in gaps and correcting facts concerning her second and third visits to America. | 2007 November | 15 | 3 | 29 to 32 |

| The fifteenth variation: A portrait of Edward Elgar. Transcript of a BBC broadcast (12 May 1957) | In Elgar?s centenary year, the BBC broadcast a programme presented by Alec Robertson. This transcript contains the contributions of Carice Elgar Blake and May Grafton; Julius Harrison and Sir Percy Hull; Sir Barry Jackson; Astra Desmond and Sir Steuart Wilson; Lady Hamilton Harty; Yehudi Menuhin; Harriet Cohen; Sir Adrian Boult and Bernard Shore; Sir Compton Mackenzie; Sir Arthur Bliss; Dr. Ralph Vaughan Williams. | 2007 November | 15 | 3 | 33 to 44 | |

| McBrien, David | Revisiting "The Hut" | A continuation of the article in 15/2. | 2007 November | 15 | 3 | 45 to 46 |

| Rushton, Julian | Elgar and academe: Dent, Forsyth, and what is English music? (Part 1) | Edward J. Dent?s essay on English music in Guido Adler?s Handbuch der Musikgeschichte (1924, 2nd ed. 1930) contains views which caused a furore among Elgar?s friends and admirers. He considered Parry and Stanford in detail, but other composers received less attention. Dent?s work follows the chronological pattern of Cecil Forsyth in his History of music, some of which is inaccurate. Forsyth?s writing on Elgar is often dismissive and he bends biological chronology to suit his admiration for Parry and Stanford. | 2008 March | 15 | 4 | 27 to 32 |

| Neill, Andrew | Dame Janet Baker's Sea pictures | The London Philharmonic Orchestra and the Elgar Society co-operated in a concert of Elgar?s music to celebrate the 50th anniversary of Elgar?s death. The concert, on 23rd February 1984, was a great success and was broadcast by Capital Radio. One of the items was Janet Baker singing Sea Pictures and it is this recording which appears in the LPO boxed set reviewed in the November 2007 issue of the Journal. In the absence of a master tape, Andrew Neill?s off-air recording was used for the set, with much improved sound. | 2008 March | 15 | 4 | 15 to 16 |

| Kelly, Tom | Yorkshire light on the first symphony | The Yorkshire critic Herbert Thompson (1856 to 1945) was present at the first performance of Elgar?s first symphony in December 1908 and at eight further performances the following year, all conducted by either Elgar or Richter. He kept detailed records of the timings of each movement, which allows comparison between the two conductors and with Elgar?s own recording. | 2008 March | 15 | 4 | 17 to 25 |

| Ling, John | The prehistory of Elgar's "Enigma" | In March 1890, The Musical Times published an article which speaks of "enigmas and...dark sayings". It is possible that the unsigned article was written by Joseph Bennett, who had used the phrase "dark sayings" elsewhere. Both terms are familiar to Elgarians and both have Biblical antecedents. It is worth exploring the possibility that Elgar was aware of these terms before he came to write the Enigma variations and quoted them in the knowledge that Bennett would appreciate the joke. | 2008 July | 15 | 5 | 8 to 10 |

| Hodgkins, Geoffrey | Andrew Neill: a tribute to the retiring Chairman | Andrew Neill joined the Elgar Society in 1966. Since his initial election to the London Branch committee, leading to his becoming the Society?s Chairman in 1992, he has made an enormous contribution to the work of the Society. In particular he has facilitated an impressive number of recordings of Elgar?s music and was largely responsible for resurrecting the publication of the Elgar Complete Edition. | 2008 July | 15 | 5 | 11 to 16 |

| Boutwood, Duncan | Gerontius as ammunition? A newly discovered letter | A handwritten letter from Novello & Co. to the critic Herbert Thomson was found in a miniature score of The Dream of Gerontius. In it, Henry R. Clayton explains that the plates used to produce the miniature scores were in Germany a few days before war was declared and had probably been used for making ammunition. Fortunately, these fears were unfounded. | 2008 July | 15 | 5 | 17 to 20 |

| Golding, William | Byron Adams's "Dark saying": A critical response | A response to an earlier article | 2008 July | 15 | 5 | 20 |

| Rushton, Julian | Elgar and academe: Dent, Forsyth, and what is English music? (Part 2) | Edward J. Dent?s essay on English music in Guido Adler?s Handbuch der Musikgeschichte (1924, 2nd ed. 1930) was written with a German readership in mind. Dent implies that Elgar?s music is not ?academic? in the strict sense, yet at the same time dismisses the chamber music as ?academic? and ?dry?. His contradictory writing seems to complain about powerful emotions in Elgar?s music while ignoring the strong appeal of such music to English ears. Part 1 appears in 15/4. | 2008 July | 15 | 5 | 21 to 28 |

| Norris, John | Tales from the complete edition, or, What did Elgar write? | Elgar?s orchestration of his work With proud thanksgiving has been recorded, but the original military band arrangement seemed not to have been performed. A collection of Elgar?s arrangements in the British Library includes separate arrangements of the work for brass and military bands, but these are in the hand of Frank Winterbottom. It appears that Elgar wrote only the short score, leaving Novello to commission a full arrangement. | 2008 November | 15 | 6 | 16 to 17 |

| Nolan, Lucy | People and places behind Elgar?s violin concerto (Elgar Society Prize) | Various people and places influenced Elgar in his composition of the concerto; their inspiration and assistance was of great importance. A reprint of the Elgar Society Prize essay. | 2008 November | 15 | 6 | 18 to 24 |

| Riddle, Emily | Elgar?s cello concerto, a personal response (Elgar Society Prize) | It is almost impossible to communicate the feelings of beauty and sadness aroused by playing this work. To play such music, it is necessary to be more than merely an instrumentalist. Many great players have contributed to the history of the music. A reprint of the Elgar Society Prize essay. | 2008 November | 15 | 6 | 25 to 30 |

| Payne, Anthony | The 2008 A.T. Shaw lecture: Completing the Crown of India | As part of Elgar?s 150th anniversary season, the Elgar Society commissioned Anthony Payne to reorchestrate those parts of Crown of India that survive only in a piano reduction. Elgar wrote the music for a masque to celebrate the 1911 Durbar; the libretto was by Henry Hamilton. Elgar arranged a suite for orchestra, but reorchestrating the remainder involved Payne in making difficult decisions. | 2008 November | 15 | 6 | 9 to 15 |

| Foreman, Lewis | Picturing Elgar and his contemporaries as conductors: Elgar conducts at Leeds | The only illustrations of Elgar conducting in his prime are sketches in local newspapers, particularly those made during the Leeds Festivals. Viewing these against illustrations of earlier conductors allows an appreciation of Elgar?s technique and charisma. Once photography became the norm, postcards, although popular, were generally portraits. It was only after the Great War that conductors were photographed posing with the baton. | 2008 November | 15 | 6 | 31 to 46 |

| Halls, Steven | Let beauty awake: British Library symposium | This symposium was held in November 2008 to consider the influences of literature on Elgar and Vaughan Williams. Speakers included Hugh Cobbe, Stephen Johnson, Michael Kennedy, and David Owen Norris. Richard Hickox, the Elgar Society?s president, spoke about conducting British music. The memory of this is made the more poignant as it was only 24 hours before his sad and untimely death. | 2009 March | 16 | 1 | 6 to 8 |

| Crowther, Anne L. | Alfred Rodewald and the Liverpool Orchestral Society | Elgar?s friend Alfred Rodewald was an early conductor of the People?s Orchestral Society. The orchestra included a number of professionals who were not paid for their performances with the society. After the change of name in 1890, Rodewald worked to improve the orchestra. Music performed included the premieres of Elgar?s first two Pomp and circumstance marches. After Rodewald?s death in 1903 he was replaced by Granville Bantock until the orchestra was disbanded in 1909. | 2009 March | 16 | 1 | 9 to 14 |

| Hunt, Donald | Elgar and the Three Choirs Festival | The young Elgar regularly played violin in the Three Choirs orchestra in Worcester. The relatively low standard of much of the music performed may have fired his ambition to write music more worthy of such a festival. His first commission was for the 1890 festival. He wrote the overture Froissart, but this was not taken up by other orchestras and it was some years before a choral work, The Light of life, was commissioned. He became a great influence on the festival in spite of writing so few works specifically for it. | 2009 March | 16 | 1 | 15 to 26 |

| Marshall, Arthur | An unusual view of Elgar | An anecdote relates that one of Elgar?s favourite recordings was of Cecily Courtneidge and Jack Hulbert. It is amusing to think of the great Elgar enjoying the same music that the author often played in his youth. | 2009 March | 16 | 1 | 27 to 29 |

| Foreman, Lewis | Elgar and Cowen?s fifth | The second movement of Frederic Cowen?s symphony reminds the listener of the textures in Elgar?s The Wand of youth. Is it likely that Elgar heard, or even played, this symphony? | 2009 March | 16 | 1 | 31 to 32 |

| Smith, Mike | Friends revisited: An edition of Elgar Birthplace EB722 | EB722 is Elgar?s MS draft of notes for inclusion in the player to piano rolls of Enigma variations. Comparisons between these notes and the booklet My friends pictured within show marked differences. The notes and commentaries printed on the rolls themselves are difficult to read accurately and there are questions as to when the notes were written. Study of all these sources, and the various accounts of them, affects our hearing and understanding of the variations. | 2009 July | 16 | 2 | 5 to 21 |

| Freed, Stuart | Elgar in Birmingham | The first major Elgar work to be performed in Birmingham was The Black Knight in 1895. In the following years his music was often heard there, including several first performances and commissions for the long to established Birmingham Festival. In 1905 he gave the first of a series of rather controversial lectures at Birmingham University as the first Peyton Professor of Music. He resigned in 1908 but continued his connection with the city by writing music which included The Apostles and The Kingdom. | 2009 July | 16 | 2 | 23 to 36 |

| Weir, John S. | I scramble through things orchestrally: Did Elgar really dislike the piano? | During Elgar?s lifetime the piano was at the centre of domestic music making and the Elgar family business. It is therefore surprising that he wrote so little for the piano and it has become widely believed that he disliked it. This view probably originated from the fact that Elgar disparaged composers who wrote their orchestral works at the piano; he also complained of the need to provide piano transcriptions of orchestral works. His reluctance to write for the instrument may have stemmed from what he saw as his own shortcomings as a pianist. | 2009 July | 16 | 2 | 37 to 44 |

| Maidment, Ted | Summer repose: The Elgar birthplace statue | Jemma Pearson?s sculpture of Elgar, commissioned by the Elgar Society, is now installed in the garden of the birthplace. It shows Elgar, aged about 40, sitting on a seat in a relaxed pose and looking out over the Malvern Hills. | 2009 November | 16 | 3 | 7 to 8 |

| Bird, Martin | Music in Worcester, 1860?1890 | Worcester had a thriving cultural life in the 1860s to 1880s, although some years were better than others, and some venues were less than ideal. The young Elgar took part in many activities promoted by local musical organizations. Historical and recent photographs show the fate of some former musical venues. | 2009 November | 16 | 3 | 9 to 32 |

| Drysdale, John | A matter of wills | Examination of four wills sheds new light on the Elgars? financial circumstances. Two of the wills are those of Alice Elgar?s mother and Alice?s aunt, Emma Raikes; they show that Alice gave up a great deal in marrying Elgar, although it is not true that the aunt cut her out completely. Alice?s and Edward?s wills provide details of their relatively small estates. | 2010 March | 16 | 4 | 5 to 8 |

| Burrows, Donald | I feel that what I saw is really worthless: Elgar and the Chapel Royal part-books | When Elgar was appointed Master of the King?s Music, most of the functions were ceremonial and concerned practical music making. There was, however, some responsibility for the King?s Music Library, deposited at the British Museum. Elgar was involved in assessing a large collection of music which was no longer used at the Chapel Royal. After much correspondence and many delays, the music was added to the collection which is now in the British Library. | 2010 March | 16 | 4 | 9 to 22 |

| Walters, Frank | Some memories of Elgar | Frank Walters was the son of a Malvern contemporary of Elgar. He remembers walking with Elgar and visiting London for Menuhin?s recording sessions for the violin concerto. His daughter adds her grandfather?s memories of Elgar talking about the "secret" of the Enigma variations. | 2010 March | 16 | 4 | 23 to 27 |

| Neill, Andrew | All at sea: Elgar, Kipling and The Fringes of the fleet | In November 1917, Kipling withdrew his assent for the continued performance of Elgar?s settings of his poems. It is generally accepted that the main cause for this decision was the death of Kipling?s son John, but examination of the background to the songs suggests additional reasons. | 2010 March | 16 | 4 | 29 to 35 |

| Norris, John and Moore, Jerrold Northrop | Tales from the complete edition. II: The Starlight Express | The publication of this volume of the Elgar Complete Edition has taken much longer than expected to produce. Initial work showed that much greater co-ordination of the music with the original play was needed in order to produce as accurate a version as possible. This proved to be complicated and time consuming, but the finished product justifies the extra effort. | 2010 March | 16 | 4 | 36 to 44 |

| Bird, Martin | Harleyford: Precursor of Hoffnung | The Harleyford Musical Festival was a spoof programme concocted by Elgar for house guests at the 1909 Hereford Musical Festival. One of the items refers to the heckelphone, an instrument included in the orchestra for Delius?s Dance rhapsody to be performed in Hereford, and also to Delius?s wallet being stolen. | 2010 March | 16 | 4 | 45 to 46 |

| Harvey, Brian | Elgar?s will: Further enigmas | Study of Elgar?s will seems to show his contradictory nature, and raises questions about the copyright status of some material. Contrary to Elgar?s predictions, the value of performing rights and other income was of greater benefit to his heirs than was formerly supposed. | 2010 July | 16 | 5 | 3 to 6 |

| Reynolds, Arthur | The King and the troubadour: Edward VII & Edward Elgar | Comparison of the lives of Elgar and Edward VII show that they had much in common, and that they each reached their peak at around the same time. After the King?s death, Elgar continued to respect George V but bemoaned his apparent lack of taste in music. | 2010 July | 16 | 5 | 7 to 34 |

| Langfield, Valerie | A young friend of Elgar: Alban Claughton (1876?1969) | Alban Claughton was the grandson of the first Bishop of St. Albans. Elgar knew and encouraged him, and later commended him to Dr. Charles Buck when he moved to Giggleswick. In later life, Claughton befriended many musicians, especially Roger Quilter, from whom he inherited an important collection of MSS and scores. | 2010 July | 16 | 5 | 35 to 40 |

| Norris, John | Tales from the complete edition. III: Hope and glory? It?s the Pitt?s | Production of a complete edition throws up several dilemmas, particularly when full scores were uncompleted or lost. Inclusion of subsequent "completions" depends on how much original material has been used. Research into the existence of orchestral parts can lead to other discoveries, for example Elgar?s orchestration of the hymn tune Darwell. | 2010 July | 16 | 5 | 41 to 46 |

| Kay, Robert | Prolegomena to the Acuta Music King Arthur suite | Elgar's incidental music for Laurence Binyon's play, Arthur: A tragedy, is the last unpublished Elgar work of any consequence. The publication of a full orchestral version of the suite from the incidental music makes a practical amount of the music available for concert performance. | 2010 July | 16 | 5 | 47 to 49 |

| Norris, John | Tales from the complete edition. IV: "It isnae her" - Elgar, women and song | Elgar?s feelings for various women are reflected in much of his music, particularly his solo songs. His wife, Alice, provided words for several songs, and singers such as Muriel Foster were also sources of inspiration. In 1930 he set It isnae me, by Sally Holmes; the romantic inspiration appears to have been Joan Elwes, the soprano who premiered the song. | 2010 November | 16 | 6 | 41395 |

| Rushton, Julian | Elgar and academe. III: Grove and Tovey | Donald Tovey, well known for his musical analysis, was principally a musician. His admiration for Elgar?s music shows in his writings, which began as programme notes for the orchestral concerts at the University of Edinburgh. The two were on cordial terms, and Elgar conducted the LSO at Tovey?s first public performance of the Brahms B flat concerto. | 2010 November | 16 | 6 | 15 to 20 |

| Mitchell, Kevin | Elgar and Hampstead | Elgar lived at Severn House in Hampstead from 1912 to 1921. Designed by Norman Shaw, it provided an impressive London base for the Elgars and was visited by many famous musicians. World War I had an impact on their time in London and Elgar still longed for the countryside. | 2010 November | 16 | 6 | 21 to 31 |

| Newton, Carl | Massive hope: A historian?s view of Elgar?s first symphony | The symphony received over 80 performances in its first year, but very few by 1911. It has been suggested that the national mood affected the popularity of the work, but this is not necessarily the case. Comparison shows that subsequent major works were also well received, in spite of Elgar?s assumptions. | 2010 November | 16 | 6 | 32 to 43 |

| Kay, Robert | The full orchestral score of the Severn suite | Elgar?s manuscript full score of his orchestration of the Severn Suite has been missing since the 1970s. It has now re-appeared and has been added to the Elgar MSS in the British Library. | 2010 November | 16 | 6 | 44 to 46 |

| Norris, John | Tales from the complete edition. V: A Pageant of Empire | There is much confusion over the number of songs included in this work. The "Pageant" was a cultural epic, lasting three days, which took place in Wembley Stadium, and included historical tableaux and music specially written by many composers. Of Elgar?s music, the Empire march is best known, while most of the songs are largely unperformed. Various listings and sources have been used to determine which songs were intended for this event. Most of the orchestral material has not been traced and it is probable that some accompaniments were never written. | 2011 April | 17 | 1 | 4 to 14 |

| Rushton, Julian | Tales from the complete edition. VI: Music for strings | Volume 24 of the Complete Edition contains Elgar?s music for string orchestra. The sketches for Sospiri indicate that it was intended as part of the slow movement of a longer piece for violin and piano. Parts of the Serenade appear to have originally been drafted for string quartet. | 2011 April | 17 | 1 | 15 to 17 |

| Allen, Kevin | A letter and a poem unmasked: Two documents from John Bridcut's film Elgar: The man behind the mask | In 1931 Elgar met Vera Hockman, a violinist, and they became very close. After Elgar?s death, Vera wrote a letter to Elgar recalling their relationship. The other item in question is an untitled poem by Alice Elgar beginning Thy love doth fade. As it is undated, the reason for writing it is unclear, but it illustrates the quality of some of her writings, which should be studied further. | 2011 April | 17 | 1 | 18 to 21 |

| Bird, Martin | A very good idea at the time: Sir Edward Elgar - Principal conductor, London Symphony Orchestra | In 1911 Elgar was appointed as Principal Conductor of the LSO, one of several distinguished guest conductors. After initial success, the appointment did not end well, and he was not re-engaged for the 1913/14 season. No correspondence has been preserved, but there are enough primary sources to enable a comprehensive picture to emerge. | 2011 April | 17 | 1 | 22 to 36 |

| Lloyd, Stephen | Did Elgar achieve a century? | It has often been stated that Elgar?s first symphony received about 100 performances during its first year. Various writers have identified up to 82 during 1909. It has now been possible to identify 83 performances within a year of the December 1908 premiere, and there may be at least three others, but it seems unlikely that the figure will reach 100. | 2011 April | 17 | 1 | 37 to 40 |